A voice to European stakeholders on soil knowledge

How soil knowledge flows to stakeholders? What are the challenges related to the soil sensed by stakeholders? What are the barriers and opportunities to optimise soil knowledge?

Researchers from EJP SOIL reached out to stakeholders across Europe in order to get answers to these questions.

Highlights from European stakeholder consultation

- The priority soil challenge across Europe is to increase soil organic matter and conserve peat soils. The second most important soil challenge is to improve water storage capacity.

- Similar views on the major barriers affecting soil knowledge management were observed among stakeholders coming from different regions across Europe.

- The priority barriers are the lack of research funding and communication.

- Three important needed actions were identified: (1) the proper development of new soil knowledge; (2) the effective sharing of soil knowledge; and (3) the actual use and valorisation of the outcomes from soil research by transferring key soil management knowledge to end-users.

Soil knowledge is important for climate-smart sustainable soil management

Agricultural soils need to be sustainably managed. The climate-smart sustainable management of agricultural soils is perceived as the central strategy to improve soil health. Soil health is an integrative property that reflects the capacity of soil to respond to agricultural intervention so that it continues to support both agricultural production and the provision of key ecosystem services (Kibblewhite et al., 2008). Sustainable Soil Management, together with the restoration of degraded soils and the improvement of soil productivity have been identified as key action areas towards the achievement of important Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this context, advancing soil science research can greatly contribute to bridge the gap between soil science and societal needs. Regarding agricultural soils, the question is ‘how farmers, scientists and advisors can collaborate, renegotiate existing and co-create new meanings for soil erosion and soil conservation’ (Schneider et al., 2009).

The EJP SOIL (2020–2025) was launched with the aim of building an integrated European research community on agricultural soils, and enabling an environment that maximizes the contribution of agricultural soil to key societal challenges such as food and water security, climate change adaptation and mitigation, biodiversity preservation and human health. Beyond performing dedicated research activities to i) create new soil knowledge, EJP SOIL aims to optimize all the phases of soil knowledge management, such as ii) knowledge harmonization, organization & storage; iii) knowledge sharing & transfer; and iv) knowledge application (Dalkir, 2005).

Soil-related stakeholders are central actors in climate-smart sustainable soil management. In EJP SOIL all soil-related stakeholders are welcome and there is a subscription on the website permanently open (https://ejpsoil.eu/stakeholder-portal/become-a-stakeholder).

Using a common methodology framework with participatory multi-stakeholder consultations in 20 European countries, EJP SOIL researchers collected the perceptions of stakeholders on how to optimise the management of soil knowledge in a view to leveraging strengths and opportunities, thus contributing to overcoming barriers and addressing identified soil challenges.

There were 314 stakeholders consulted that included scientific researchers (29%), farmers and farmer associations (25%), public administrators (15%), agricultural schools (2%), NGOs (1%), and agro-industries (1%). European countries were grouped into geographic regions. Of the total stakeholders that answered, 27% were from Central Europe, 26% from Northern Europe, 22% from Western Europe, and 21% from Southern Europe. There is no gender equality since 61% are male and 35% are female.

What are the challenges related to the soil sensed by stakeholders?

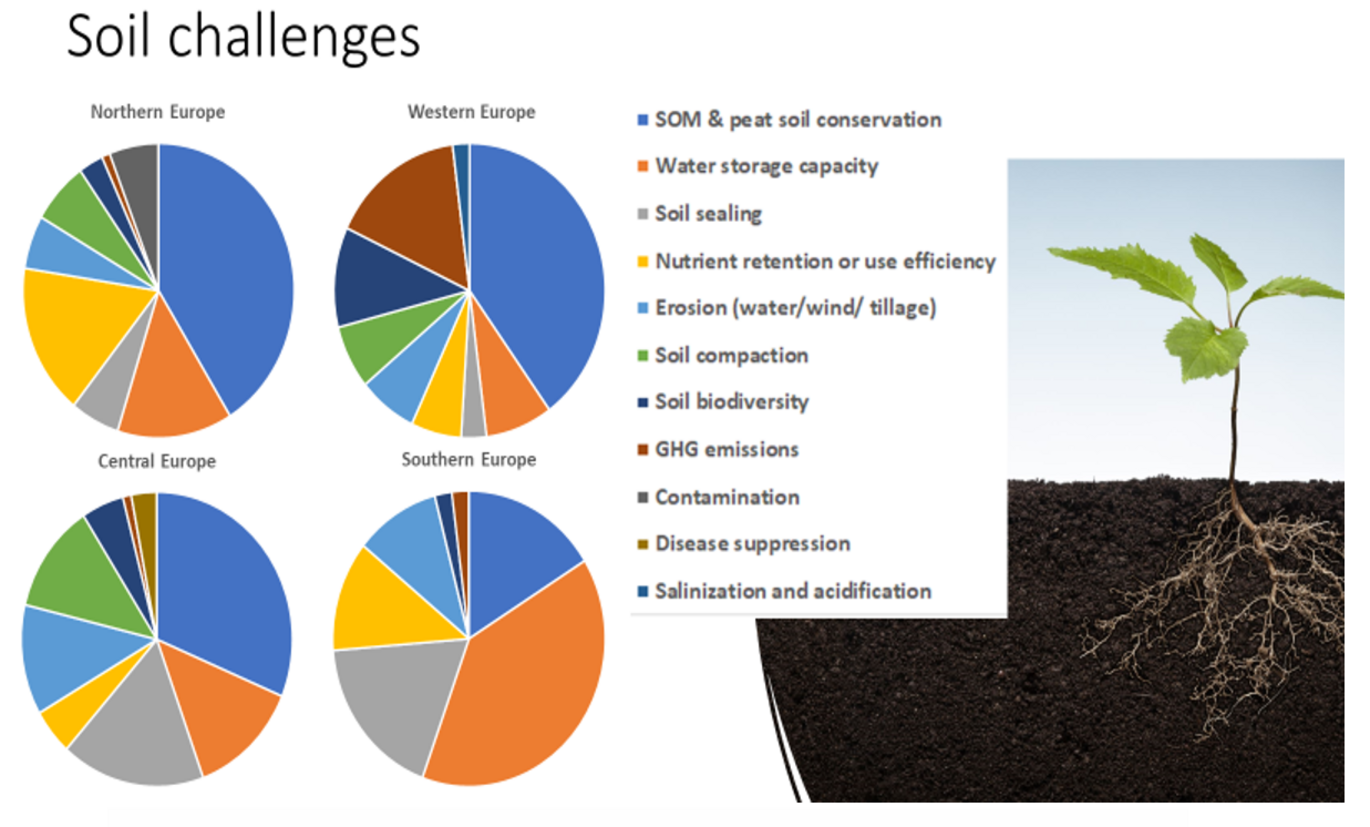

Stakeholders prioritise pre-identified soil challenges for their own country, ranking them from 1 (low priority) to 10 (high priority). In this way, it is possible to evaluate the weighted importance of each soil challenge among the countries grouped into European regions (Figure 1). The results show that “improving soil organic matter and peat soil conservation” was the priority (17%), followed by “nutrient retention” (14%) and “improving water storage capacity” (13%). In southern European countries, ‘improving the water storage capacity’ of the soil was considered the top priority.

What are the barriers and opportunities of soil knowledge management?

From this stakeholder consultation, soil knowledge management in Europe faces 102 barriers and has 107 opportunities identified as suitable to overcome them. Stakeholders were asked to identify barriers and opportunities concerning the 4 phases of soil knowledge considered by EJP SOIL: development, harmonization, sharing, and application.

Stakeholders from Southern Europe listed the highest number of barriers followed by Central and Northern Europe (Figure 2). Regarding opportunities, stakeholders from Central Europe identified the highest number, followed by Northern and Western Europe. The majority of the barriers and opportunities are identified in the phase of development of new knowledge in soils followed by soil knowledge application.

Overall, numerous and highly diversified types of barriers and opportunities were identified and grouped into seven main categories: “Capacity building”, “Technical”, “Networks”, “Communication”, “Economic”, “Political”, and “Social”. The majority of the barriers and opportunities identified are capacity building, technical, networking, communication, and economic. Barriers and opportunities of social nature were only reported in soil knowledge application and in sharing and application phases, respectively.

In the soil knowledge development phase, the major barriers identified were related to capacity building. From the twenty-seven barriers indicated, the first four represented 41% of the responses ‘lack of relations among research, advisory services and farmers’, ‘financial resources allocated to soil research are not sufficient’, ‘lack of public-private partnership on soil research’, and there is ‘lack of training for advisors and farmers on soil-related issues’. The opportunities seen by stakeholders to overcome such barriers collected 48% of the responses. In detail, stakeholders indicated that there is the need for ‘increasing funding for soil related research’, ‘supporting multi- and trans-disciplinary research’, and to ‘activate/valorise/fund long term experiments’.

For soil knowledge application, barriers are distributed over all the seven categories, but especially in the political, capacity building, and economic. To apply soil knowledge, there are four most mentioned barriers indicated by 42% of stakeholders. In detail, it was indicated that ‘yields and profits may not respond as farmers expect’, there is a ‘lack of good policies and incentives’, and ‘technological constraints’ exist. European stakeholders indicated twenty-eight opportunities, with the first three collecting 60% of the responses. In detail, the opportunities seen were the ‘development of region-specific soil management strategies’, the need for ‘good policies and incentives with effective policy measures’, and ‘farmers have adequate ICT tools and use them’.

This stakeholder consultation indicates that there is significant room for improvement concerning soil knowledge production, dissemination, and adoption in Europe. Among the most important barriers identified are technical, political, social and economic obstacles, which strongly limit the development and full exploitation of the outcomes of soil research. This study clearly suggests that climate-smart sustainable soil management will benefit from (1) increases in research funding, (2) the maintenance and valorisation of long-term (field) experiments, (3) the creation of soil knowledge sharing networks and interlinked national and European infrastructures, and (4) the development of regionally-tailored soil management strategies. All the mentioned interventions can contribute to healthy, resilient and sustainable soil ecosystems across Europe.

Although soil challenges have been largely recognized and tackled by policy strategies, recently released at European level in the framework of the EU Green Deal, they are still waiting for being translated into concrete directives, policies and measures, monitoring and evaluation systems to be adopted and transposed at national level. The outcomes of this work can guide the drawing of policies and measures fostering opportunities for improving soil knowledge toward addressing the main European soil challenges. By ensuring continuity to the European soil network and sharing knowledge platform, at the same time continuing to strengthen the dialogue between science and policy and introducing new actions to address the weak bridges currently existing at the science-to-practice interface.

For more infomation

Nádia Castanheira - Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária, I.P., Soil Lab, Avenida da República, Quinta do Marquês, 2780-157 Oeiras, Portugal.

Sevinç Madenoğlu - Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies (TAGEM) 06800 Ankara, Türkiye.

(This article summarizes outcomes of Vanino et al., 2023. Barriers and opportunities of soil knowledge to address soil challenges: Stakeholders’ perspectives across Europe. Journal of Environmental Management, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116581)